King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table: half-stitched of the Otherworld, half-dragon by design, and fully embodied with a higher ideal to protect and serve Camelot. Batman: modern-day royalty, an American billionaire, repeatedly saving his city from destruction in the guise of a symbol, and without a personal stake in glory or other ego-related gratification. The dragon-embodied Superman: often hidden in plain sight as Clark Kent. The Doctor and his TARDIS, only revealing that which is heroic in the immediate context of its use. Daenerys Targaryen: while she plays the ‘game of thrones’ with a war fashioned from fire and blood, she is royal in the truest and most divine sense: kind, just, and ultimately fair, yet fully emerged and prepared to take the proverbial or literal throne. These are only a few of our dragon heroes. What is it that sets them apart from the rest? And, some would argue, transcend their own humanity?

To many, a hero is primarily defined by his humanity, which ultimately compliments his abilities, intent, and deeds. In ideal terms, the humanity of a hero is the seed of compassion and care, consideration for his fellow man, bestowing upon him a sense of honor and appropriate pride; connectivity to the proverbial heart. In more realistic terms, heroism is constantly at odds with human nature, which often counters that ideal with a certain brashness, inappropriate pride, and an overt conformity to the desires of the ego – selfishness to the extreme – even in the midst of what could be, or actually are, acts of greatness. A human hero is too often flawed – a hero who, at some point in his journey, will fail us, and himself, in favour of the preservation of his ego.

To answer the question of what informs, and separates, a dragon hero from a human one, we must look backwards to ancient myth, the purest manifestation of both human and dragon heroes given to us over time.

Steeped in humanity, with the exception of his god-like strength, is Hercules/Heracles.

Considered to be one the greatest of all mythological heroes, Hercules is primarily known for his supernatural physical superiority, and his indomitable ego. His supernatural strength, coupled with his confidence and force of will are often cited as his greatest virtues. His is the story of perseverance and accomplishment by way of a relentless approach; if we put our minds to something, we can do anything.

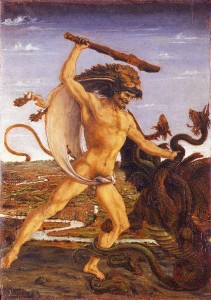

To others, Hercules is set above the rest because he enjoys a uniquely one-sided relationship with the Otherworld and with the gods and beings who inhabit that space just outside the borders of a rational human perception of reality. In stark contrast to other mythical heroes who typically receive guidance and help from the Otherworld as they go along on their quests, Hercules is at war with it. He blunders blindly through it, smashing things with his club; like a playground bully he intimidates, demands, grabs, draws with his sword, cuts and kills. His great physical strength his only answer, and his only remedy.

Hercules and the Hydra, Antonio del Pollaiolo c.1475

Hercules is our best example of human hero gifted with inhuman strength: he is not the example of his own ideal self, not confident, not self-reliant, and not brave. He is arrogant and dismissive, an egotistical imbecile, forcefully crashing through all obstacles – perpetually destroying. Through all his journeys and countless opportunities, he does not grow in any psychological or spiritual sense, nor does he gain or exhibit any divine understanding. No lessons are learned. No transcendence is achieved. Hercules is the embodiment of an ego’s triumph over the ideal, thus remaining one-dimensional. A hero whose static ego is at odds with his developed strength. He is ego without balance, teetering on the brink of madness and finally succumbing to it – body, mind, and spirit.

All non-dragon (human) heroes, from antiquity to modern times follow this path, failing to posses these key qualities that can serve to prevent a self-destructive end.

Opposite of Hercules is Theseus. When Theseus enters the labyrinth, he listens to the advice given to him. When in the Underworld, he does not demand, trick and smash. Instead, he apologizes to Persephone. Likewise, Perseus accepts help from Athena and Hermes on his quest to behead Medusa. Theseus primarily fights humans who prey on and terrorize other humans. Like Clark Kent, he frequently travels without revealing his royal identity. He fights the Minotaur not to save himself, like Hercules, but to save the lives of young man and women. Altruistic motives or at least fighting for a purpose, a good greater than themselves, is a hallmark characteristic of dragon heroes – an element not present or obscured by ego to dysfunction, in their human counterparts.

The pattern of venerating a hero’s humanity (positively and negatively) over all life in his path is often overwhelming, and not constrained to ancient myth. For example, Blade, the modern human-vampire hybrid, is a human hero because he chooses to keep his vampiric nature suppressed while dedicating his life to the extermination of vampires in favor of humans. A hero by way of choosing humanity and embodies a human-centric perspective found in most modern heroism today. Entitlement and a narrow purpose also prevail in this arena: Arguably one of the most well known heroes, Captain America is transformed from a frail young main into a god-like creature but remains subsequently confined within his previous and constant way of thinking. Only seeming altruistic through physical empowerment, he is still fighting exclusively for a singular and familiar American paradigm, with no tolerance for any other vision, growth, or divergence from that path – at least in the early incarnations of the protagonist. Even the early Superman, beloved by millions within his mythology, is beloved foremost for his human-centric agenda and philosophies. The newer and more alien version of the hero was all but rejected by audiences in last summer’s Man of Steel, for being presented as more godlike than human; colder, foreign and largely without his familiar alter ego – the mild-mannered and unobtrusive Clark Kent.

© Marvel Comics

To the non-dragon, the human hero, despite his flaws, is the acceptable and preferred version of the hero, because he is relatable and familiar. But to those who are dragon-minded, the hero enmeshed within his own human nature is incomplete. Often arrogant and ignorant, eternally at odds with his own faults and shortcomings, he has failed to experience what is arguably the most important of all the non-physical aspects of transformation found in the complex architecture of the hero’s journey: Ego-death, or the Dark Night of the Soul.

Daenerys Targaryen and the loss of her family and reign. Batman and the death of his parents. Superman and the loss of his home planet, biological family, and then (in some versions) his human father. Theseus’s loss of his identity. The death of King Arthur to become the Once and Future King. The Doctor’s annihilation of Gallifrey and the genocide of his people. All are manifestations of ego-death, the crumbling loss of the superficial constructs that we use to define ourselves outwardly – the death of ego to reveal the stronger, purer foundations of self.

A greater victory is won by the dragon who has undergone the quest of ego-death, a transformation measured more in ripples and everlasting change than in unfathomable bloodshed, or muscle tone, and victories that truly matter only to a few. At the journey’s end, he is transformed from into something wiser, less mortal, making way for aspects which are immortal, and therefore unbreakable.

To look at it another way, Captain America, having never lost the construct of his (Americanized) ego, despite his physical transformation, does not meet the requirements of a dragon hero in early incarnations. However, following the “deathblow” dealt to American ideals during the period of 911, he would have experienced ego-death and been able to complete his transformation, being reborn into a post-911 world and forced to rebuild a purer ego, enabling him to visualize an America free of any empty or illusory patriotic concepts. The modern incarnations of the myth (Captain America and The Winter Soldier) may very well be the manifestation of the long-awaited evolution of the Captain, bringing him back into line with Campbell’s pure mythology, and enabling him to complete his own hero’s journey.

The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their place.

Plutarch’s Life of Theseus

Dragon-embodied heroes can be identified by behaviors that look entirely different from their human-embodied counterparts because prior to their transformation into a superhero, their human egos have been, like the Ship of Theseus, split apart and rebuilt – through the process of ego-death. They behave differently because, simply put, they are different. Ego-death in a dragon hero informs not only a unique understanding of the Otherworld, but an ability to traverse it in harmony and without conflict; it is in their nature. Ego-death and the destruction of the human construct enables the dragon-born hero to accept the help and guidance of all manners of inhuman creatures: fairies give directions, magic potions and slippers, and invisibility cloaks, gods regularly grant protection, dragons hide them in their caves or fly them to unreachable lands, unicorns lend their backs to cross enchanted forests, and so on. Even goblins have been known to unlock secret underground passages when the dragon hero requires it. And, all the while, this hero is learning and undergoing a deep transformation and rebuilding – the extent to which he is oftentimes not fully aware of.

Like a shaman, from birth the dragon hero has the potential to simultaneously see and accept multiple realities, this World and the Otherworld, but it is ego-death that allows him to accept and move between them. He ultimately discovers and refines his abilities as he endures a necessary form of education, manifested through trials of the quest, seeing it through to initiation. This is symbolized by the lowest point of the journey, when the quest seems hopeless and the hero’s death certain, but he survives due to the proper application of the knowledge and power gained along the way. Thus, the end does more than justify the means; the means, the dragon hero’s experiences and actions along his journey, are as vital to his growth and goals as the prize itself. This triumph is not that of the ego. In fact, because the dragon hero’s ego has already died at the lowest point of the journey, the triumph of the dragon hero is wholly without ego.

Randy Julien May 18, 2014 at 5:02 pm

Dragon-minded heroes.